I think it’s about time the WWW started getting better typography controls in CSS. If you look at what typography designers can do in print applications like InDesign, the typography capabilities in CSS are still relatively primitive especially in the context of responsive design.

In the late 90’s as a beginning web designer, I would always have to tell my boss (a very experienced typography designer) that the things she wanted to do with type just wasn’t possible. It’s now 2022 and many of those things still aren’t possible (though we do have web fonts now at least.) I’ve been waiting for decades for some of these typography controls to come to CSS standards and web browsers, so maybe if I describe them properly, someone will notice. (Now this is also on the CSS working group Github.)

Runts

CSS still has no runt controls. A runt is when a paragraph ends with one word on one line. It’s very ugly. In print design software, we can fix this procedurally by selecting the last X number of characters using a GREP style and applying a no-break attribute to them. So if I set the last 15 characters to no-break in a paragraph, that will make the last 2 or 3 words stay together and therefore stay on the last line no matter what the container’s width becomes. This is not possible in CSS, but I think it should be.

The syntax could be something like:

p:nth-last-char(15) – selects the last 15 characters of a paragraph.

p:nth-first-char(15) – selects the first 15 characters of a paragraph

Then we could have something like below that applies the nowrap white-space attribute to the last 15 characters of a paragraph:

p:nth-last-char(15) { white-space: nowrap; }

/* keeps the last 15 characters of a paragraph from wrapping to another line */

One current work around for this is to add a </br> break tag before the last two or three words in a paragraph and use media query breakpoints to apply “display: none” to the </br> tag in instances where the paragraph width does not create widows on the last line. This requires manually adding the BR tag to content in the database and also requires manually measuring which media query breakpoints should activate or deactivate the work-around. That’s way too much work for something that can be automatic with a GREP rule in InDesign.

Paragraph composer

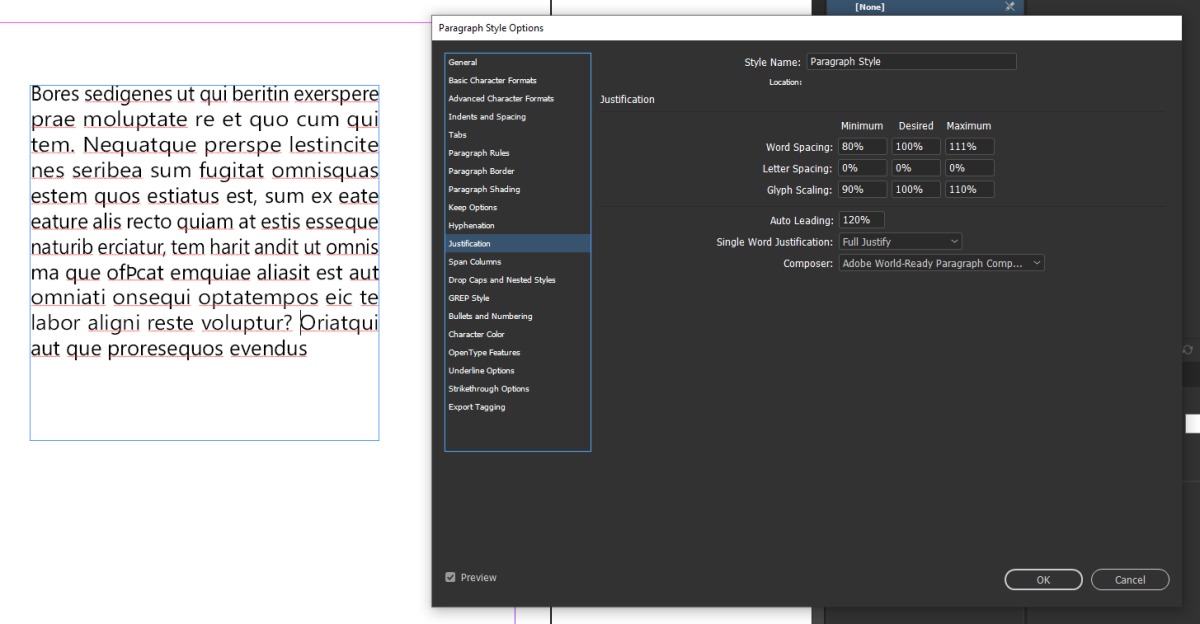

Another issue in WWW typography is in the ragging of text on each line. There are no decent controls for this. With InDesign, I can choose from different automatic paragraph composer settings and then I can tweak the minimum and maximum variations for things like word spacing, letter spacing, and glyph scaling.

The syntax could be something like:

p { paragraph-composer: multi-line-composer;

word-spacing: mindesiredmax(80%, 100%, 110%);

letter-spacing: mindesiredmax(-5%, 0%, 5%);

glyph-scaling: mindesiredmax(90%, 100%, 110%); }

The CSS word-spacing property already exists, but doesn’t support any minimum/maximum variations within a multi-line paragraph composer. The CSS letter-spacing property also exists, but again doesn’t allow for variations within a paragraph according to the paragraph’s line ragging. There are no glyph scaling properties in CSS.

A balanced rag between lines in a paragraph is ideal in terms of typography and this is done by increasing or decreasing word spacing, letter spacing, and glyph scaling on a line-by-line basis in order to decrease the differences in line widths and make a more pleasing paragraph shape.

Via Github:

Re. your issue with ragged-right lines, you didn’t mentiontext-align: justify– I presume you’re aware of that?

Justify paragraph alignment is something different, but should also use the paragraph composer options, plus the character spacing, word spacing, and glyph scaling min/max values.

Justified paragraph text on the web currently adds space between words such that the first word and last word of each line are aligned to the width of the paragraph. On the web, this causes ugly “pigeon holes” of unbalanced white space within the paragraph. This is also bad typography design as the holes don’t indicate anything of importance like the end of a sentence or new paragraph or such. They require the eye to move random distances in order to keep reading and create distracting aesthetics.

In the above screenshot, you can see Chromium on the right rendering some text with the “justify” alignment attribute. The same text on the left is in InDesign also with the “justify” alignment attribute but with a multi-line paragraph composer and some min/max settings for word spacing and character spacing. You’ll notice the InDesign typography is a bit better than the web browser’s typography since the spacing within each line is much more balanced due to the subtle variations in word and character spacing.

Now, in the above screenshot, some glyph scaling min/max values were added to the paragraph on the left. The changes in width to each letter are very subtle, but this makes for a much better paragraph shape with no massive “pigeon holes” at all. This is superior typography design than what is available in web browsers at the moment. However, sentence beginning/ends are not obvious in that paragraph, thus the need for a sentence spacing control in order to improve sentence skimming and readability.

Sentence Spacing

Nobody does good sentence spacing in typography design anymore, so very few people probably even know about this aspect of typography design. Many people these days follow the convention of including only one space between sentences. For paragraphs with shorter sentences, this reduces the number of visual “pigeon holes” that may clutter the paragraph. However, with longer paragraphs filled with longer sentences, the single space between sentences makes the paragraph more difficult to read. Thus the smart way of typography design is to increase the space between sentences within longer paragraphs, while reducing the sentence space between shorter paragraphs.

See the advice given by Philip Luckombe in The History and Art of Printing (London, 1771):

Another rule that is inculcated into beginners, is, to use an m quadrat [i.e., an em-quad] after a Full-point [period]: but at the same time they should be informed, not to do it, where an Author is too sententious, and makes several short periods [sentences] in one Paragraph. In such case the many Blanks of m-quadrats will be contemptuously called Pigeon-holes; which, and other such trifles, often betray a Compositor’s judgment, who may be a good workman else.

I’m not sure what the syntax for a sentence spacing control should be as ideally we should have selectors to control shorter sentences separately from longer sentences. Perhaps the selectors can be defined by sentence character count. Currently we have no CSS selector for sentences at all, nor do we have any attribute for controlling the space between sentences. Maybe something like

p:sentence-char-count(minmax(3, 30)) { sentence-space: 1em; }

/* selects sentences with 3 to 30 characters, applies 1em of space between sentences. /*

p:sentence-char-count(minmax(31, auto)) { sentence-space: 1.5em; }

/* selects sentences with minimum of 31 characters and no maximum, applies 1.5em of space between sentences. /*

Who else is sick of bad typography?

Do the people in charge of creating new CSS standards just not know about good typography design? At the very least, I wish all of the typography controls available in InDesign were also available in CSS with future web browsers. The web has been the future of publishing since the turn of the century, but typography design on the web isn’t even up to speed with the 16th century.